The Fly Your Satellite! Design Booster is a pilot program of the European Space Agency (ESA). It’s aimed at students working in the design of a CubeSat mission. CubeSats are miniaturized satellites that have standardized form — in LEGO brick fashion, they’re shaped as $n \ge 1$ 10cm cubes, stacked vertically. It’s an idea to accelerate and democratize space missions1, cutting down on the cost2 and effort required to get the spacecraft in-orbit.

Design Booster aims to assist the teams by providing further training during the full project lifecycle and across a wide spectrum of areas from aerospace engineering to project management or even operating the CubeSat while it’s in-orbit. The program is split in distinct phases that are adapted from the typical development cycle of space missions and it follows a fixed scheduled spanning 1.5 years.

In brief, the teams first have to apply to the program. Then, the shortlisted teams undergo the “Training and Selection” phase where they receive training from ESA experts and in about a month after they have to defend their proposed design in front of a panel of ESA experts. The selected teams continue on to the next phase, “Baseline Design Review” where they have to baseline their design which is then assessed by the experts. After this two-month phase is concluded, the teams have about a year to finalize their design. The program ends with the so-called “Final Design Review”, where the design undergoes through examination to check whether the design has been successfully consolidated.

Getting There

The “Training and Selection” phase kicked off with presentations from ESA experts in Nov. 7. I was invited to give a talk to share some insight on how working at a long-term space mission project can be, with an addendum on the challenges behind trying to run Space Biology experiments inside a CubeSat. I flew from Greece to Munich, Munich to Amsterdam, took the train to Leiden and there I was on a rainy day!

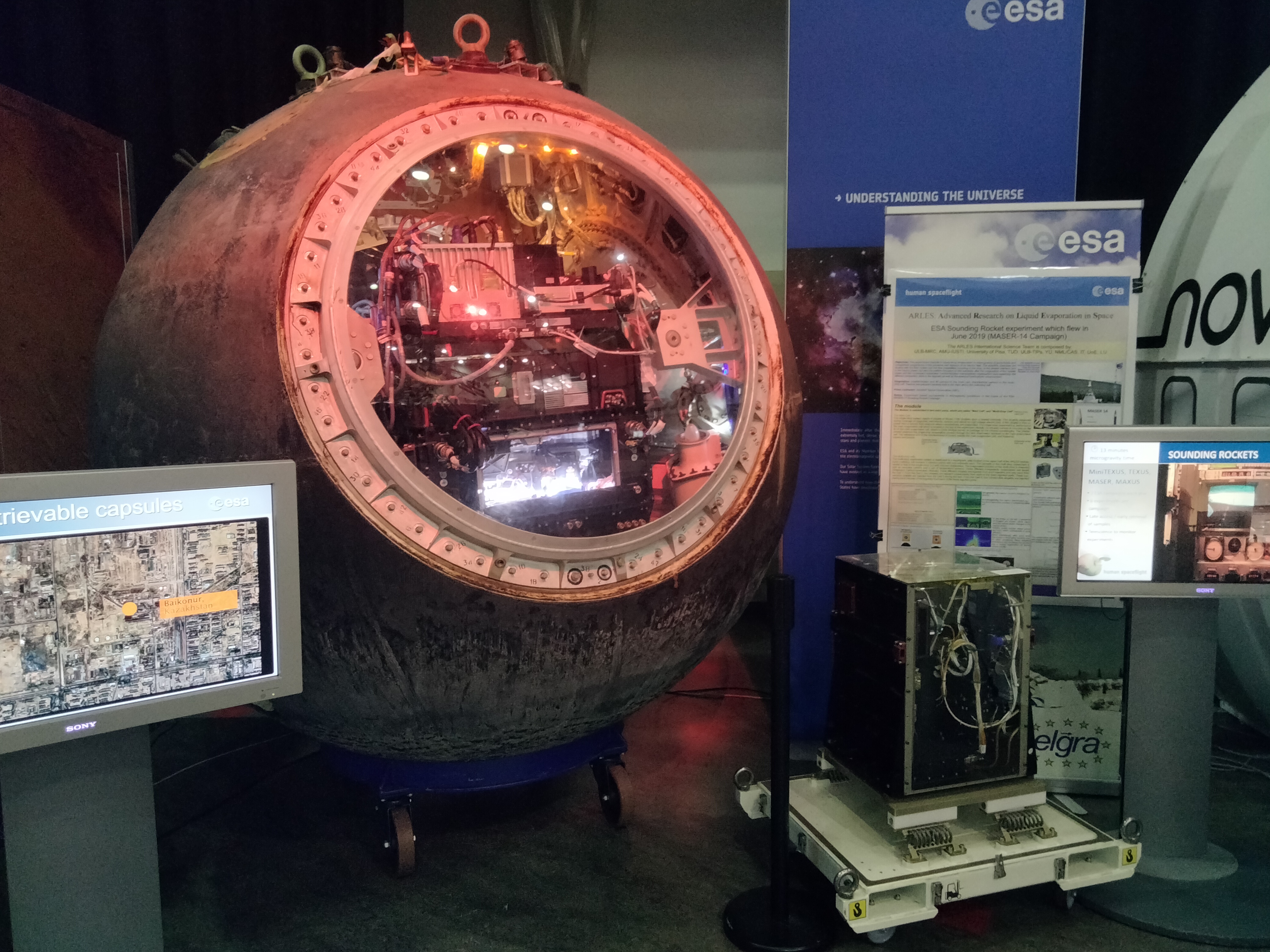

The training workshop was hosted in the ESA ESTEC facilities. ESTEC is in Noordwijk, a small town by the sea somewhere in the Netherlands. It’s the larger site and the technical heart of ESA. I got to navigate through the facilities inside an autonomous shuttle bus you could drive with a joystick and a touchscreen!

When preparing the material to share, I asked myself: how can I help the candidate teams as much as possible in such little time? I decided to structure my talk loosely, with some tips clustered into overlapping categories. I’ll try to roughly recollect some of the material below.

Refresher

I come from Greece and I’m the co-Science Lead in the AcubeSAT project. AcubeSAT is part of the Fly Your Satellite 3! program. I’ve been involved in this effort since almost the very beginnings, when everything was still at a nascent stage. I’m currently getting to wrap up my studies, and I’ve joined the team not long after I enrolled in the university, I’ve worked in different aspects of the project, technical and not, and currently I’m responsible for the science-y stuff.

The AcubeSAT nanosatellite undertaking began late 2018. We’ve designed and are developing a 3U CubeSat which holds a 2U biology payload. Our mission is two-fold: we want to establish our idea for a modular platform to perform space biology experiments in CubeSats/small satellites as a working prototype. Also, we aim to probe the way conditions in LEO (mainly microgravity and cosmic radiation) affect yeast cells at the gene expression level.

To achieve the mission goals, the 2U payload is a pressurized vessel which hosts a container with the various compartments to run our experiments. We’ll culture cells in-orbit and then see how their gene expression is altered through acquiring images via our DIY microscope-like imaging system. We aim to run the same experiment in three distinct timepoints across the duration of our mission, and to do this we’ve been using a small platform called a Lab-on-a-Chip to hold the cells and interface them with the various fluidics in a miniaturized version of a biology lab.

Our high-level roadmap is roughly the following: We’ve submitted our proposal in October 2019, took part in the selection workshop hosted here in December 2019, got accepted in February 2020, submitted the TS-VCD in April, submitted the first version of CDR in October and had it approved in September 2021, marking the end of the design phase and the beginning of the construction/testing phase. Right now we are getting ready to run a series of testing campaigns at the ESA facilities, then pass the MRR and be in-orbit by late 2023/early 2024.

You can check out more about AcubeSAT in GitLab.

Project management

There’s always exceptions to rules.

Learn the rules like a pro, so you can break them like an artist

— Pablo Picasso

Don’t take what I write as a hard absolute to be followed. It’s empirical data gathered through observation. Think about what I write and try to understand why I write it.

Things are tough

When you find yourselves in such a project, things can be tough. Why? Well, for starters: You have to develop skillset from zero — not just on the technical side, but mostly on the organizational. Almost everything is behind closed doors, you don’t even know what’s out there, you have to learn but how? You have to find support (e.g. from the university). You have to ensure infrastructure (e.g. machines). This might be something very generic to get prototypes, might be something very specific related to your payload. Getting access to required infrastructure might be almost trivial in some cases, near impossible in others. You’ll face this sooner or later, start thinking about it as early as possible.

So what can you do other than resort to self-sarcasm as a coping mechanism? Invest in open-source and the community. There’s people you can learn from, if not teach. Akin’s Law 43:

You really understand something the third time you see it (or the first time you teach it.)

Our team has benefited greatly from open-source and open science. In any case, do some research and see what’s out there. Fly Your Satellite is about CubeSats. CubeSats are very affordable and easy to build and verify, which means in turn that they are very approachable and that a lot of people who might be able to help you do not belong in the space industry, meaning there’s a wealth of information that isn’t as strictly regulated.

Remember that you get help from ESA and the experts. Reach out — there’s a lot of experience that you can’t find elsewhere. Don’t be afraid to ask because it might seem like you haven’t done your homework. Keep in mind that it’s an educational program and that they want you to succeed. They’ve went through the whole journey multiple times. This is very crucial to take advantage of as early as possible. They won’t just help you solve problems, they might give you fundamentally new ideas and paths to explore. Lastly, other teams participate in FYS!, be in touch. In other FYS! versions and other related projects, too. All in all, we’ve helped and received a great deal of help.

Scale up

There’s no leadership outside of the team, the organization has to be DIY. That might very well be the biggest factor towards your success. No one will help you, and you won’t have expertise. It’s one thing to learn how to blink LEDs, and another to learn how to run a team of 40 people to meet strict deadlines in a very demanding project.

COVID-19 hit, and it hit hard. Why am I saying this? Because it’s a good segue. We had to rethink our organizational structure due to limited physical access. We found a hybrid scheme to work best 3. You’ll eventually have to scale up, time and time again. How? Your organization must not only stand the test of “now”, but also be future proof.

Make sure to find good infrastructure, platforms, especially for organization. I can’t stress this enough. Communication, tracking and finding information, project planning and management. Don’t be pushing things back because you have a deadline to meet. Don’t be afraid to invest early, plant the seeds; they will bloom later. Try maintain information transfer at all costs — that was our biggest problem. Documentation is the best remedy to said problem. As per Akin’s Law 22:

When in doubt, document. (Documentation requirements will reach a maximum shortly after the termination of a program.)

Organization: the small

Keep minutes, have agendas, don’t recycle topics, end each topic with an action, make the most out of a meeting. Cross-team meetings are very important. Hold concurrent sessions, frequent meetings, be transparent always.

| ✅ Do meetings when: | ❌ Don’t do meetings when: |

|---|---|

| People are feeling lost | There’s technical work to be done. Ask people to document, unless they need extra motivation |

| For teambuilding activities | For brainstorming. If you have to, make sure that there’s enough preparation beforehand |

| For weekly sessions that promote team coherency and updates | There’s people waiting for other people. Extremely inefficient, people get bored |

| For feedback sessions | When people do nothing during the meetings and actions are not taken |

| You are unsure of next steps | When meetings are the “excuse” for you to feel productive |

Text can often be hard, but text is king. It stays forever, you can quickly reference it or look it up at a later date, it can be used as training material, it can be used to explain concepts to new members without the need of constant supervising. It saves time and effort, while talking can be an inefficient back-and-forth if you’re not careful about it.

… and the big

You need SYE, aka systems overview. Regarding management, always see the forest, not the tree - how do all the pieces interact with all the other pieces? Always be wary of cross-dependencies. Constantly track things, move deadlines appropriately, be on top of things. You’ll come to find out that you’ll be setting a deadline and it will be way overdue and then you’ll have to set a deadline anew — do that.

Be agile, especially in the beginning. Find what’s good for you. Understand why it’s good for you. Self-reflection is the most important thing. Explore a path that you might later on decide that you won’t follow, play with the design, the structure, be bold. Akin’s Law 11:

Sometimes, the fastest way to get to the end is to throw everything out and start over. You have time, you can afford to make mistakes.

Calm down

You’ll screw up, constantly. Relax and learn from it. We’ve had so many situations where things almost derailed and came close to crumbling down because people were losing their minds. Relax, be calm, assess the situation, do your best, learn from any mistakes and move on. In the grand scheme of things, it probably doesn’t matter that much. Diffuse situations, avoid crowd mentality. We’ve had “critical” situations dozens of times, we’re still here. Remember, everything’s gonna be alright.

If it isn’t, not to worry. It’s an educational program. I’m not trying to set the bar low here, things are very challenging and you should strive for excellence, but you have to understand the nature of the program. You have to understand that the ESA people are here to help and that they know you will commit a lot of mistakes. The thought that they expect you to make mistakes is very liberating, because you will make mistakes and you might think that the consequences will be way bigger than they actually will be.

Plus, having a problem is great because you know that something is wrong, you probably know what it is, and you will eventually figure out a way to fix things. That’s way better than sitting awkwardly, wondering whether there’s a problem looming around the corner waiting to bite you when you’re not looking.

Try to build a momentum, expect a momentum to be built. Then, ride it, but guide it too — don’t let it carry you. I keep saying that things are difficult — you’ll find it difficult at first in various areas, for example when deciding on the organizational structure. It will require a lot of effort in the beginning. It’s like a slope where, if you’re doing it right, little by little it will get easier with time.

Our case happened after we delivered the first CDR version successfully. Things somewhat got automated, everyone knew what to work on, communication was frictionless, new members were seamlessly integrated. No matter what, you have to always keep things in check and constantly revisit. We didn’t and cracks started to appear soon enough; it cost us a lot in the end.

The bus factor

Be afraid of the bus factor. The bus factor is a crude way to assess how important someone is for the project. The way you do that is you ask yourself, “what if this person was to get hit by a bus tomorrow?”. You will come across it. Some times there won’t be a lot you’ll be able to do to mitigate it. But also always remember: no one is irreplaceable. Each time we chose to keep tolerating people that didn’t abide by our collective’s rules, it never worked. You’re capable, don’t forget that. Also trust your gut, like you should do in interviews.

This is a very long-term project, it therefore transcends individuals. As already stressed, always, always think about the long-term. Have a plan B, C, D, … (even about design, even about people). A phrase of a friend that I feel encapsulates all of this well:

It’s a marathon, not a sprint

… but there will be sprints ;)

Problems

Always find the next generation that will succeed you and/or your peers. Do that preemptively. Otherwise, it will be too late and you’ll be patching holes. We’ve faced this problem multiple times. More often than not, there’s a bigger underlying problem, and it has to do with structure. People are usually not the source of the problem. Don’t be too eager to blame something on an individual, dig deeper.

But people can be the source of the problem. Never underestimate that. Especially if they are in a position of power, either organizationally or due to technical expertise. Don’t endow with power lightly:

With great power comes great responsibility

— Uncle Ben

We’ve had that problem happen way too many times. It’s better to leave a gap than to shoot yourself in the foot this way.

People management

People can also be tough

Again, there are a lot of difficulties you’ll face when you’re trying to get people to collaborate to see this through. There’s some questions to ponder on. How do you find someone to do the boring work? There will be a lot of it, filling spreadsheets, searching for manuals… Especially if you have to hold events and have a social presence too.

It’s a demanding project without short-term tangible rewards (monetary, ECTS …). So how do you get people to do unpaid work? They’ll do it if they want to do it. Therefore, you have to make sure they want to do it a lot.

How do you get ordinary people to do the extraordinary? You’ll have to face great technical challenges. At the same time, you’ll have to constantly support and get the others pumped. You’ll have to be there to mediate in case any conflicts occur, etc.

Taking initiatives is vital — that has been an area where we often are lacking as a team. There’s new ideas someone has to think. There’s work that no one will do unless someone decides to take it up by themselves. It also helps tremendously in fostering an environment where people feel their peers are motivated. Building a DIY arcade cabinet can also help you, check ➡️ 4.

How do you ensure meeting participation? Remember that you should think about how you approach these things too. A good example and place to start might be 5. This is recommended for you to see that there’s a lot of thought that can go behind all this. Meetings facilitate collective intelligence. Have you thought about that? 6 There’s a lot of different ways you can approach people and people-problems.

Physical presence is vital. Expand beyond the scope of the project. Hang out, do cool things on the side. SpaceDot is to me something way, way more than just the project. I’ve learned a ton, met cool people, made friends, found out what I want to pursue in academia, and more. And this is what’s kept me working in the project for so long :D

If you want to go all the way, go all the way. The project requires heavy investment. It will take a toll. It will also overlap with other areas of your peers’ lives. You have to take that into account and learn about their life in order to effectively support them. This goes hand-in-hand with forming groups and being part of a gang, crew, band, squad, syndicate.

Talk!

Always face your problems, always speak, always communicate. Hoarding problems under the rag instead of facing them is a very well known human tendency :P Communicate problems to ESA. Again, they’re here to help. The sooner they learn about something the better. They’ll always appreciate you being upfront, trust me. Don’t put yourselves inside rabbit holes you’ll then have to dig out of.

Feedback is crucial, it’s all about feedback cycles 7. Heed this. Feedback requires good communication channels, so first build these. Then learn to give feedback. Learn to receive feedback. Provide people with a lot of different ways they can give feedback. Make sure that there’s always more than one person (which ideally occupies a different position in the team) for someone to speak to. Feedback cycles is the way we get better. Again, make sure to do everything you can to have people giving feedback, as well as receiving feedback and acting on it.

Praise in public, blame in private

Well, not always but you get the idea.

The leadership behind the leadership

Set up a “core” group of people to serve as the backbone of the team at all times. This is, organizationally, mainly what helped us make it. It also affected our progress severely when we lacked it.

Who thinks about the team and not just technical work or events? That’s how you can find the people you’ll rely upon. Decisions will always upset some people. The question is which.

If all goes south, side with the ones that will carry the team on their shoulders. They’re your most important asset. Always consider how a decision might affect them and their motivation. Invest in those you believe will carry the team forward, not from a technical viewpoint. This might mean not siding with the majority. The majority will also blindly follow whatever, if you give it enough time.

But! Don’t shadow-government much — this all goes against being transparent and people will eventually catch up. Be transparent, it almost always pays off.

Help them help you

People won’t do things they don’t want to do forever. Never forget that, always try to find them an alternative. Wisdom has it there’s always someone out there that wants to work on what you don’t. Find them. Newer members might find something more exciting. That’s good resource allocation. Don’t shy away from talking to your peers about non-technical issues. You can always help them learn how to work more efficiently, for instance. A good example would be a talk on building a second brain.

Help them help you: Vol 2

Don’t leave anyone on their own. Define group tasks. Set small, well-defined tasks. Make the members feel and visualize the progress. Make sure everyone is on the same page regarding the high-level roadmap. Give people things they might not love but that are important, and things that aren’t important but they love doing 8. Progress is seldom linear, or apparent. Try to make it apparent, but have that in mind. Involve people and throw problems at them (but always be there when needed). Don’t be afraid to throw problems at them, that’s how they grow.

Space Biology Payload Challenges

- Miniaturization of cell culturing instrumentation: you’ll need temperature control, storing growth medium on-board, a place for the waste to go (not necessarily), a platform to host the organisms…

- Ensuring biocompatibility of payload materials: not a major challenge, given that there is a variety of biocompatible materials and that you’ll usually be isolating the biology, e.g. in a millifluidics card. Still, it’s something that will affect a lot of design and implementation decisions.

- Regulating temperature and pressure to decouple cell survival-behavior from other space stressors (e.g. radiation): controlling for pressure is by far the biggest hurdle to overcome here, since it means you will need the container that hosts the biology to be pressurized, which, in space terms, means you’ll have to persuade people to let you test and fly a ticking bomb that can go off at any time. Also you’ll have to make sure it doesn’t leak and more :)

- Using methods for autonomous measurements (e.g. spectroscopy, microscopy): well it’s difficult to find instrumentation that is small, robust, and to somehow invent a way to automate the whole process so it doesn’t require (physical) intervention.

- Preparing predictable long-term biological sample storage methods before launch: You can see 9 for a great example.

- Engineering reliable readouts for cell viability/metabolism.

- Standardization of common wet lab methods to meet space engineering requirements/procedures.

Teams

12 teams developing a CubeSat were shortlisted to participate in the “Training and Selection” phase:

- 6S by PoliSpace: flight-proof and characterize solar cells and structural battery payloads. From Italy, affiliated with the Polytechnic University of Milan, 1U.

- AlbaSat — Italy, affiliated with the University of Padua.

- Antaeus led by the LIP i-Astro group: measure intense gamma ray sources in the 100 keV - 10 MeV. From Portugal, affiliated with the University of Coimbra, 2U.

- Astrojam by the Aerospace department of the University of Nottingham: GNSS interference mapping and characterization payload. From UK.

- BioSat by Orbit NTNU: sustain a plant in SSO (400-600km). From Norway, affiliated with the Norwegian University of Science and Technology.

- BIXO by UVigo SpaceLab: probe quorum sensing in bacteria inside millifluidic cards. From Spain, affiliated with the University of Vigo, 2U.

- Estigia by the Valencia Polytechnic University: AI chatbot for the public to communicate with the satellite. From Spain, 2U.

- LEDSAT 2 from [S5Lab](Sapienza Space Systems and Space Surveillance Laboratory) - Italy, affiliated with the Sapienza University of Rome

- ROSPIN-SAT-1 by ROSPIN: monitor Romania’s health vegetation status. From Romania, affiliated with the Polytechnic University of Bucharest, 3U.

- SAGE by ARIS: generate milli-gravity and probe its impact on the senescence of primary cell lines. From Switzerland, affiliated with ETH Zurich, 3U.

- ST3LLAR-Sat1 BOIRA by UC3M: measure atmospheric humidity primarily in European regions. From Spain, affiliated with the Charles III University of Madrid, 2U.

- TRACE by TUDSAT: test retroreflector-based satellite identification strategies. From Germany, affiliated with the Technical University of Darmstadt, 1U.

Having the opportunity to get to chat with some of the people working in these projects was a great experience. It made me especially happy to see that more research groups are trying to take a jab at developing a satellite that will host a biology payload for in-orbit experiments! We’ve maintained communication with some of the teams and I’m eager to see what you’ll announce during your upcoming PDRs.

You can take a look at some group photos in this ESA article.

Outro

My very condensed personal story about FYS! is something along these lines: During high school, or what I like to call “the dark ages”, for various reasons I didn’t have strong goals or motivation. When I entered the university, I felt for the first time in my life that this is a new chapter, a new beginning. Every new beginning holds a lot of power — and there I was, moving immediately to a new town.

While I didn’t have any particular background, I was very motivated, so I put in the effort during the classes. However, I soon discovered that I wanted something more than what seemed to me as school with extra steps. I joined some teams here and there, mostly as a software engineer, tried to work on projects with supervising professors etc. It was good for a while and I learned a lot, but what I wanted was to be in an environment where people around me would be passionate.

Long story short, I managed to get accepted in SpaceDot, when the project was just about starting. I suddenly found myself in an environment where the ones next to me where motivated, passionate, had dreams and were willing to put in the extra work to see their goals come to fruition. I made a lot of friends (and not only), drank beers and had great fun. I found friends that shared my dreams and, more importantly, my fears. Friends to play games and do stupid side projects with. Friends that are still by my side to this day.

Not all was easy of course, we had our fair share of fights, of dead ends, of seemingly impossible problems, of sleepless nights to submit the proposal on time or tiring months to get everything ready for CDR. There were others that didn’t want to help or that actively dragged us down. Trying to undertake such a project is very difficult as is, trying to undertake it while being a student in Greece is a lot harder: we had to conjure money and expertise out of thin air. And this was exactly the strong bond that kept us all together.

I was there for others and they had my back, we stayed awake at nights together, we hanged together, we faced our demons and grew together. Undertaking a project just to put it in your CV isn’t bad per se, but it seems if you want to chase the big challenges, you can’t do it alone. It’s not the CV that keeps you on track while you’re in the trenches, it’s your friend that has worked more than you have for the same dream that you’re trying to accomplish.

Sometimes it is the people no one can imagine anything of who do the things no one can imagine

— Alan Turing

Why should you do all of this? Well, give it some time, love it enough and you’ll join the game. I shared my story, give yours form. Getting to actively participate in a very demanding, large scale (40-80 teammates) project is rare. Working on a long-term project with a mission at the interface of seemingly unrelated fields as a student is more rare. What’s even more rare is the freedom of choice you’ll have when trying to make things work in a project such as this one.

FYS! is an invaluable opportunity for you to grow as a person and to inspire others along the way. Its scope expands way past getting your CubeSat to fly. You’ll give form to a common vision — we wanted to bring Aerospace to Greece, and it seems like we’re doing just that.

ROSPIN is an NGO birthed in Romania with the overarching goal of developing the Romanian Space ecosystem. We’ve helped them with SYE, OBC, had some general chats and even had a team member come visit our lab. By the way, the team behind their first project, the ROPSIN-SAT-1 CubeSat, took part in the training week at ESTEC. PETRI is a new ESA program where accepted students receive training and can submit an experiment proposal. The experiment can be performed in one of ESA’s altered gravity platforms, like the ISS or during a parabolic flight. This came in Nov. 6:

Above all, it’s rewarding and a ton of fun:

If it’s not fun, why bother?

— Reggie Fils-Aimé

Have fun.

Poghosyan, A., & Golkar, A. (2017). CubeSat evolution: Analyzing CubeSat capabilities for conducting science missions. Progress in Aerospace Sciences, 88, 59-83. ↩︎

Sweeting, M. (2018). Modern small satellites-changing the economics of space. Proceedings of the IEEE, 106(3), 343-361. ↩︎

Retselis, A. F., Papafotiou, T., & Kanavouras, K. (2022, April). Adaptation of the AcubeSAT nanosatellite project into remote working during the COVID-19 era. In 4th Symposium on Space Educational Activities. Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya. ↩︎

Clair, J. S. (2011). Project Arcade: Build Your Own Arcade Machine (Vol. 52). John Wiley and Sons. ↩︎

Goleman, D. (2017). Leadership that gets results. In Leadership Perspectives (pp. 85-96). Routledge. ↩︎

Cooren, F. (2004). The communicative achievement of collective minding: Analysis of board meeting excerpts. Management Communication Quarterly, 17(4), 517-551. ↩︎

Hattie, J., & Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback. Review of educational research, 77(1), 81-112. ↩︎

Alon, U. (2010). How to build a motivated research group. Molecular cell, 37(2), 151-152. ↩︎

Santa Maria, S. R., Marina, D. B., Massaro Tieze, S., Liddell, L. C., & Bhattacharya, S. (2020). BioSentinel: long-term Saccharomyces cerevisiae preservation for a deep space biosensor mission. Astrobiology. ↩︎